Salam!

Today I met the five people I will be spending the next six weeks with (and their 5-year-old neighbor). I played mime. Kindergarten Arabic script books were involved.

But we won’t start there. In fact there is an entire day in between that still must be addressed.

Wednesday morning began with preparation for the arrival of our home-stay families. A brain aching two hours of what is easily becoming one of the most beautiful languages I’ve ever tried to speak. Already I am in awe of the careless way pedestrians throw a hard H and sweet LRRRR into the middle of any word. At least trying to speak Darija, or Moroccan Arabic, is turning out to be fun. I just would give anything for a better memory right now.

Later in the day, we hit the streets for a duel assignment. Our program split into groups to create a guide to the city on everything from transportation to buying textbooks (ours). We also had to practice bargaining—jargon for which we had learned the day before.

Just so you know, I hate bargaining. I always leave just wishing everything had a price-tag. I like clarity in my exchanges. So it’s safe to say I wasn’t overly enthusiastic about this experience.

But no matter how much I worry, Morocco never fails me.

It wasn’t soon after we’d left the Center that Allison and I accidently broke away from our five person group in the bustling Medina market. We had already tried and failed at bargaining once. I promise we really did try!

Having no luck with jewelry, we make our way to a shop ceiling of scarves.

“How much?” Al asks in French –a phrase I most likely forgot once again.

“100 MDH”

This is too much for our 10 MDH (about $1.20) limit.

Still we try, on and on in each shop we enter, with every non-English speaking vendor on that street. One man pulls out his notebook explaining in French and Arabic that he would in essence pay us for the privilege of taking the scarf away. Another man approaches me with big eyes, outstretched hands and a mouth-full of Arabic after my modest greeting. “No, I can’t continue this conversation in your language because yes, I am American.”

On the plus side, I brushed up on French numerals. And surprisingly, we left without a single person hating us that morning. In fact, I think it’s safe to say we made friends.

I didn’t understand what people meant when they said Moroccans are polite. The people I’ve met have been so easy to get along with. We laugh together without ever knowing exactly what the other person is saying. After an exhausting explanation of our meager funds-in which we did not buy one of his scarves-a man who owns a shop at the end of the street-and laughs in a way that stretches into his chest and across his shoulders- reached out to shake our hands and wish us a good day.

A young man with particularly good English a block away was all smiles when I said “Besslama” as we walked away, as was a woman in the bookstore across the street. Even when I mispronounce something locals are often so pleased with my attempt they’d rather laugh it off then scoff at me for wasting their time. With an environment this encouraging, I’d be content intensively studying Arabic for five hours per day (luckily we will only be doing two).

Al and I learned it’s much easier (and cheaper) to hail a cab in Rabat, but that you might have to share. Since everyone that day seemed to like us, not only did the previous passenger start a conversation with me about school, but the driver didn’t start our meter until after he dropped her off (apparently this isn’t normal).

That night when we returned to the Center, our program coordinators and amazing cooks had prepared a special final dinner for the entire group, complete with drummers.

Thursday began as just a mess of emotions. What if my home-stay family doesn’t like me? How are we going to communicate? What if they have a Turkish toilet? Luckily it ended with me exactly as I am right now. I already miss the friends I made this week (yes I’ll see them tomorrow morning), but I have no reason to complain.

My home stay family lives in a two-story house in the Medina with a pink living room and a red terrace. The houses here all follow a very similar traditional structure. They are like apartments and some are higher than others. Another student in the journalism program is my neighbor and earlier today I was called out onto the terrace to check-in as he stood below. In the living room (and in my guest room) couches line the walls. This, of course, allows for families to have plenty of people relax any way they want to as they watch TV, share meals or drink mint tea, as we did tonight, sweetened with honey and with different breads and toasts on the side.

Over tea I tried out my new survival Arabic (with a notebook cheat sheet) and found out that “study” when incorrectly pronounced, can sound a lot like “poopy”. It’s embarrassing but at least I‘m getting everyone to laugh.

When I walked in the house I immediately had a good feeling. It smelled like cleanliness. And if anyone knows my mother they would understand why that reminds me of home.

The family is comprised of three daughters. The oldest is my age and the youngest is five. Everyone is sweeter than I could have possibly imagined. “Mamma Latifa” hand fed me little meatballs out of the Tangin when she decided I wasn’t eating enough. She then gestured around the table and clasped her hands together. Looking straight into my eyes she repeated something to me in Arabic. From my right I heard the translation, “She says when you want something from the table, you take it. We are all family now.”

Sitting at the table eating Tangin with a group of Moroccans can easily give you that feeling. There are no individual plates just fruit, sides and pieces of bread you use to pinch meat and vegetables in the middle of the table. The serving dish is your plate. It’s everyone’s plate. And if I could choose any way to experience family time with my family it would be while piling large amounts of food into my mouth. Without shame. Beneen Bezzaf!

My sisters are fantastic. Not to say that my sister americania is great but to be honest she isn’t half as nice. My oldest sister is so helpful, willing to go out of her way to make sure I’m comfortable, and that includes ensuring that I have someone to talk to. My second oldest sister, slightly younger than me, speaks less Arabic, but still watches my face when I’m not looking and, like her mother, will make sure with a simple “Lebez” or “You good?” that I’m not hiding any frustrations or anxieties.

Now my baby sister. She is perfection. When I arrived she ran around me, a little shy but incredibly curious. It wasn’t until I started to try and show them my Arabic that this 5-year-old girl found her way in. Wiggling around next to me on the couch she began to have me repeat phrases after her until I understood well enough to complete what she was trying to have me say. She’d walk away and come back only to ask me again. If I got it right she’d nod with her entire body and say “Bravo!”

She’s five.

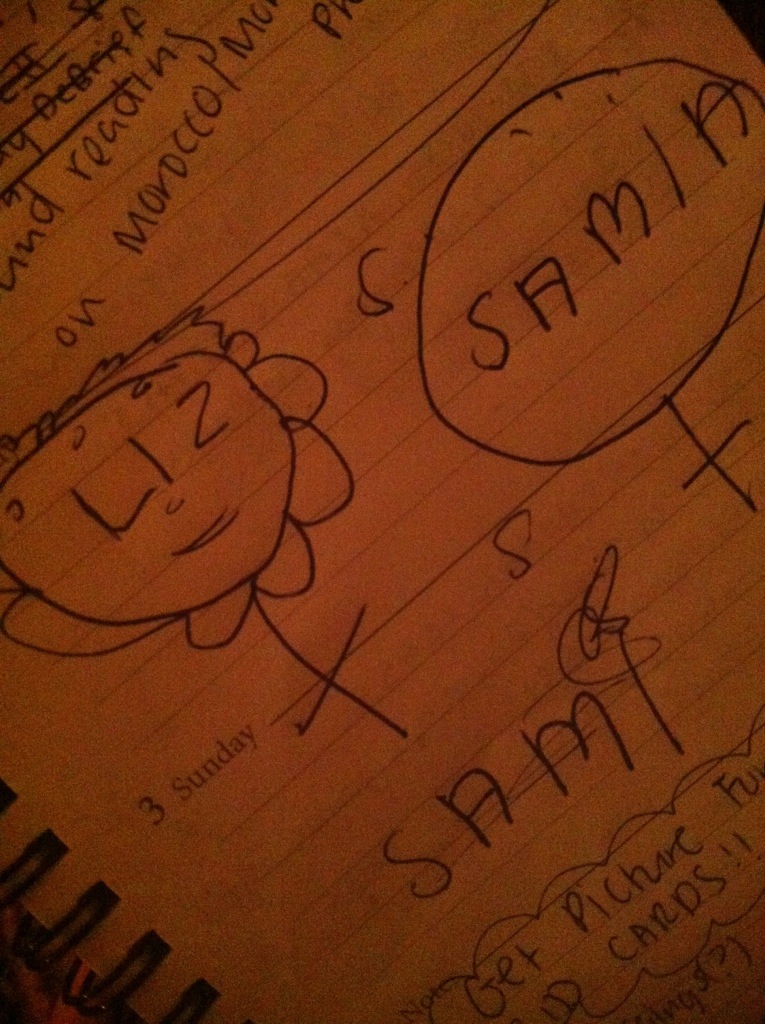

When I took out my notebook she wrote her name for me and I in turn wrote mine for her. This turned into a little game that I’ll be finding remnants of for months. Quite literally. She wrote all over my planner.

Just before bed she came down to my room again as I unpacked pointing at everything and asking “Schnoo?” She tried on my hat and lipstick and gasped when she saw my camera.

I have a little sister with two little buns on top of her head, the curly pieces falling out of a purple clip. She leads my through the Medina by the hand and tells me not to step on grates. She is my petit professor.